Credit’s Mixed Signals

Now that this decade has come to an end, it is almost unimaginable to look back to its beginning—in a world directly post-GFC—and believe the incredible run seen from practically every asset class since. Most investors who have participated in any market besides cash have done quite well since those 2009 lows. As a result, a general comfort has been setting in that no matter what happens with global trade, manufacturing, or the latest political pundit’s tweet, things will be okay—and if they’re not, the Federal Reserve will step in to fix them. In economics, this is referred to as moral hazard, which is defined as a “lack of incentive to guard against risk where one is protected from its consequences”. While in no way am I suggesting these historic markets will not continue to break new records, I do feel compelled to point out some of the interesting present dynamics which are a direct result of this golden decade.

Consider the following chart showing the effective federal funds rate since June of 2019:

As you can see, and might very well know, the Fed was cutting rates in the second half of 2019. In fact, it cut them by around a third in just a very short period of time. Mind you, this is while the unemployment rate was 3.5% and the Michigan Consumer Sentiment Index was reaching decade-level highs. This would make it seem like an odd environment to be providing stimulus to the economy. However, in its September and October comments, the Fed noted, “The global growth outlook has weakened,” “Elevated uncertainty is weighing on business investment and exports,” and “Trade wars/European elections could materially increase risks to the economy.” Perhaps not everything is as rosy as the current data suggests.

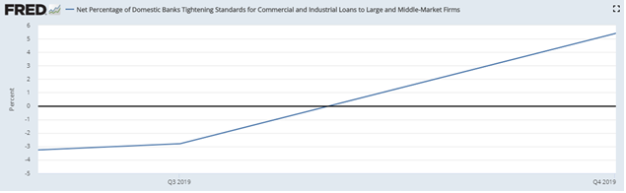

The next question is, if the Fed sees potential threats to the economy, do the actual underlying market participants agree? For this you can turn to the Fed’s conduits, the banks. The following chart shows that on average, domestic banks have recently gone from loosening their lending standards to now tightening them. A function of their confidence in the underlying borrower’s ability to repay. Perhaps it is coincident timing that this occurred alongside the Fed’s rate cuts, but I would suggest not.

Given the Fed’s concerns and the increase in lending standards by banks, one would reasonably assume that the size of the corporate credit market has been decreasing as a result. In fact, it has done just the opposite. Non-financial US corporate businesses now have a record $6.5 trillion in total debt outstanding. That is a 13-zero figure! Even more amazing is this number continues to grow:

It is important to note that even though the Fed and banks are getting more cautious than they have been and corporate debt issuance is booming, credit is not necessarily a bad investment. Spreads (the amount of yield received in addition to what you would receive from a “risk-free” treasury investment) are intended to compensate investors for all of these considerations and more. Generally, the theory suggests that the more considerations, or risk, the larger the spread to investors—which seems like a reasonable tradeoff. But, what if I were to say to you that the exact opposite was actually happening in the second half of 2019? Since June, high yield spreads have come in from 4.7% to 3.9% which represents a 17% decrease in the pricing of perceived risk:

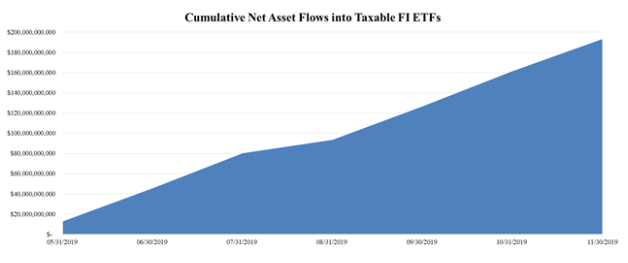

There are a few things causing this dislocation between theory and reality, though they are closely tied together. Firstly, across the globe, there is currently $12.5 trillion of negative yielding debt. This means that investors are effectively paying borrowers to hold their money for them rather than keep it in their bank accounts. With so much debt trading at such ludicrous valuations, any yield spread at all looks compelling from a relative perspective. This in turn creates a lot of demand for US corporate debt, pushing the prices higher and, naturally, the spread lower. Another related factor is the aging population in the United States. As more and more people enter retirement and look to their savings to fund their lifestyle, generating income is a dominant component of their investment decision making. Given the incredibly low interest rates set , the Fed is desperate to find other assets besides cash which can meet its needs. Hence the massive allocation into taxable fixed-income ETFs, with over $170 billion being added just in the second half of this year:

There is clearly a dislocation between what financial institutions believe is an uptick in credit risk and the pricing investors are willing to sacrifice in order to receive some yield. This relationship will eventually break as each side of the equation (higher risk and lower yield) gets more and more extreme.

While many of the comments above may seem skeptical in nature, I don’t mean to scare anyone, be alarmist , or suggest that credit is a poor investment class. However, it is important to understand that the past decade has caused some of the mechanisms in this market to flash differing signals and investors would be wise to at least stop and think about how they are currently exposed to the space.

About the Author

Alex Knapp, CFA, is a Portfolio Manager at Thomas J. Herzfeld Advisors, Inc. Before joining the firm, Alex had extensive experience across international banking, asset management, wealth management and alternative investment funds. He was formerly an investment specialist for Aviva Investors covering alternative fixed-income strategies. He also served as a portfolio manager and head of liquid alternatives for Ballentine Partners. Alex is a published contributor to Bloomberg, has been quoted in the Financial Times and has spoken at industry conferences across the country. He holds FINRA Series 65.

Citations:

ICE Benchmark Administration Limited (IBA), ICE BofAML US High Yield Master II Option-Adjusted Spread [BAMLH0A0HYM2], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/BAMLH0A0HYM2, December 9, 2019.

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US), Effective Federal Funds Rate [FEDFUNDS], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/FEDFUNDS, December 9, 2019.

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US), Net Percentage of Domestic Banks Tightening Standards for Commercial and Industrial Loans to Large and Middle-Market Firms [DRTSCILM], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DRTSCILM, December 9, 2019.

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US), Net Percentage of Domestic Banks Increasing Spreads of Loan Rates over Banks' Cost of Funds to Large and Middle-Market Firms [DRISCFLM], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DRISCFLM, December 11, 2019.

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US), Nonfinancial corporate business; debt securities; liability, Level [NCBDBIQ027S], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/NCBDBIQ027S, December 10, 2019.

https://www.reuters.com/article/us-investment-summit-bonds/is-the-end-of-negative-bond-yield-phenomenon-nigh-idUSKBN1XI0VX

Important Disclaimers: Alex Knapp is a portfolio manager at Thomas J. Herzfeld Advisors, Inc. (the “Advisor”). This article does not constitute a recommendation to buy or sell any security or asset class discussed herein. The article expresses the views of the author and not of the Advisor. Certain statements reflect the opinions of the author as of the date written, are forward-looking and/or based on current expectations, projections, and/or information currently available. The author cannot assure future results and disclaims any obligation to update or alter any statistical data and/or references thereto, as well as any forward-looking statements, whether as a result of new information, future events, or otherwise. Such statements/information may not be accurate over the long term. The views are those of the author acting in his individual capacity and not as a representative of the Advisor; in no way does this report constitute investment advice on behalf of the Advisor.